WARNING! FULL DISCLOSURES ARE INCLUDED IN THIS BLOG,

PREPARE YOURSELF IF YOU HAVE DIFFICULTY WITH EMOTIONS (and after all, what else

is a blog for?!!)

I start with the call.

On December 26, 2021 Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away. I remember this happened when I was living on the UMass Amherst campus for a hot minute (I was an assistant resident director of a dorm for a little over a month – but that is another story). Anyway, I was living in the rather large apartment designated for ARDs. I must have returned home from spending Christmas with my cousin's family in Hillside, New Jersey. This must have been a special tribute to the Freedom Struggle leader because I had returned back to the apartment after the holiday. I was soaking in the very large and deep bathtub (one of the outstanding features of the apartment) and listening to the broadcast on my phone. NPR, PBS and all public radio/television media are very creative. They often take pauses during broadcasts using music. During the Tutu tribute, the break featured the music of Bra Herbie Tsoaeli, a legend-elder jazz bassist and prolific composer in the South African Jazz tradition. It is hard to put into words the deep feeling, the soulfulness, the hope and the beauty of the music. The tenor player sounded so much like Coltrane and there were voices singing a beautiful melody. This was the call. My call. I already knew from a brief visit in 2017 that this tradition was going to be the focus of my dissertation project. But in the thick of the Fall semester of my third year of course work, I had not given the project much thought. I was just trying to power through long and difficult readings and writing papers. Bra Herbie’s melody, “Woza Moya” reminded me of my purpose for being in the PhD program…and was calling me across the Atlantic ocean into another land…into a culture and society that is a distant relative, but obviously family from the sound of their jazz, which is so much like African America’s. PBS announced that the music was from Bra Herbie’s 2021 release At This Point In Time: Voices and Volumes and that the two

different musical interludes were from the song “Woza Moya.” I must have just barely dried off from my bath before I used WhatsApp to contact my brother-friend-interlocuter Yonela Mnana about the recording. It turns out what he was playing piano on that specific track! Such a call was no accident – especially when I could, with a press of a button, get one of the musicians featured on the recording on the phone within the hour. That is what I am doing here, my fourth time in South Africa. I am answering the call of the beautiful melodies flowing from the musical mind and soul of those such as Bra Herbie Tsoaeli.

After my encounter with South African jazz just after Christmas 2021, I returned to South Africa the following summer and then from December 2022

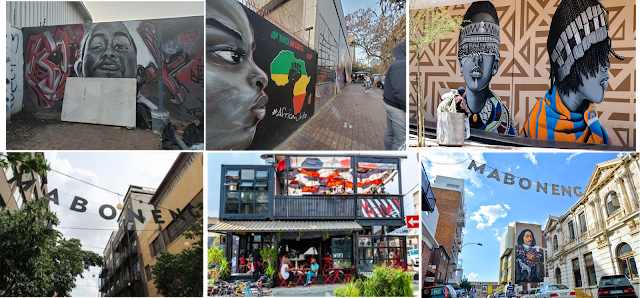

to January 2023. I lived in Braamfontein and then Mabaneng. From that time to this, so much has changed concerning my sense of home. Home.

FULL TRANSPERANCY WARNING! PREPARE TO READ IF YOU HAVE

DIFFICULTY WITH EMOTIONAL DISCLOSURES

Home for me has been a constantly changing landscape of

locations and relationships. Since I was a child, I have lived in many

different places – apartments and houses with my father, mother and sister, and

then my mother and sister. College dorms and apartments at Howard University and

apartments in New York City. I once had a home in New York and then Maryland

with my ex-husband Sheldon. We were each other’s home, each other’s family, wherever we

lived. Then…our home fell apart and ended in a painful divorce. At the end of that

process UMass Amherst and my apartment loft in nearby Springfield, MA became my new

home. And even though my blood family and I became estranged because of the fall

out of my divorce, Washington DC and the relatives living in the city remained

my home. My mother, my sister, my aunts, my cousin and my godmother. Now, all of

that is gone. When my mother became critically ill last Spring, my family splintered even more. The crisis of my mother’s stroke resulted in complete and utter familial disaster.

2 Timothy 3:23 In fact, everyone who wants to live a

godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted

Matthew 10: 34-36 Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to turn “‘a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law— a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household

When my father and my mother forsake me, the Lord will take me up – Psalm 27:10).

I realized that the best days of my family belonged to my childhood years when the elder generation was alive. I suppose that anyone who went through what I did would question where home is. When you have no more family left, where is your home?

Matthew 10:4 If anyone will not welcome you or listen to your words, leave that home or town and shake the dust off your feet.

I have become strong through the process of shaking the dust of my feet and moving forward. I know life, I know things and I know people. Pain and betrayal are strong and effective teachers.When I arrived for my fourth time in South Africa on May 23rd I was welcomed by my church family here. Home. The family of God is my home. I planned my trip so that I could participate in a Christian retreat called Family Camp. Brother Ntando from the church, and another brother, were waiting for me in the Oliver Tambo Airport lobby and welcomed me with a cheery, enthusiastic greeting that brought me relief and joy. Helping me with my bags, they whisked me into a spacious SUV and onto the highway to the home of a church sister in the northern Joburg suburb where I am staying during my time here. The highway and landscape were so familiar that it felt as if I had only been gone for two weeks. The departure point for Family Camp was my Auntie Stella’s house, a wonderful woman and a wonderful Christian who has loved and welcomed me each and every visit. She has hosted me for many lunches and visits, including Christmas and New Year’s Eve 2022. She and her husband, who is a pastor of our church, have a beautiful (and I mean beautiful) home in northern Joburg that feels like home. As I sat in the sunshine, chatting with her relatives and folks from the church who were also going to Family Camp, it truly felt as if I had never left. On our way to Drakensburg in the KwaZulu Natal province, I felt so grateful to be in South Africa again. The landscape is so beautiful - even the rest stops!

For my Family Camp weekend, I lived in a chalet with other single women. Home. As an African American I belong to Africa. I felt right at home with other Black women from Zimbabwe, South Africa and Botswana who created swirls of Black feminine beauty around me with shower soaps, skin moisturizers, perfumes, cute outfits, full figured curves, manicured nails and a variety of hairstyles, from my own kinky twists to locs, braids, and full-out down-the-back hair weaves. Mixed into this cloud of pulchritude were Southern African indigenous languages like Shona, Ndebele, isiZulu and Setswana. When I added my own African American English to the equation, we were ready for a reality tv pilot of a new series called Women of the Black World. Every time I am around African women, I learn more about my identity as an African American woman (more on this in another blog). Home.

As welcoming and loving as Family Camp was, and even being around my host’s family that arrived from Zimbabwe and other parts of the South

Africa to see a cousin off to a new job and life in Australia, once I got

settled this past few days, I started to feel seriously homesick. I

always forget this part of my South Africa visits. During my last visit, I dealt

with homesick feelings by listening to familiar audio books. I have been doing

the same this time (Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred Taylor for those

who might want to know.) But things came into focus yesterday that caused yet

another paradigm shift.

So…preshow for me Friday May 31st. This is winter in South Africa and I am once again COLD! I am used to temperature regulated environments (required by law in the United States) and there seems to be no such thing here. Not complaining : ) But my temporary home is the same 50 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) inside as it is outside – especially at night. Needless to say, on top of feeling homesick yesterday, I was also starting to feel physically sick – tired and I might have had a little temperature.

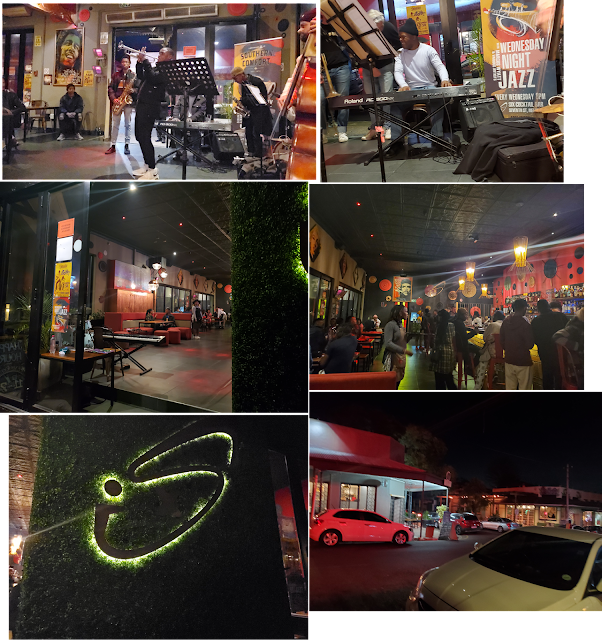

By the time I arrived at Untitled Basement, I was tired, wanted to be in bed and was only there because I promised Bra Khaya that I would be. It was 7 pm, an hour before the show was scheduled to start, and even after a delicious grilled chicken meal, I was ready to go home. Friends – all I can say is when those musicians started playing, my whole being woke up – spirit, soul and body. And what song did they start with? The same that I heard during the Tutu PBS tribute in late 2021. “Woza Moya.” The recording features a young blood, Sisonke Xonti on tenor, which was beautiful. But at this show, Khaya Mahlangu was blowing the tenor. Bra Herbie sings his melodies while playing bass and directing the band. Untitled Basement is structured in a circle in the same way our music is structured. The musicians are positioned in a circle in the center of the room, and the audience seats are circled around the band. The band played one beautiful melody after another with Bra Herbie energetically leading. Sometimes the audience sang along. The person who introduced the band mentioned that it would be a spiritual experience, which I did not take seriously. That was foolish of me. The music of John Coltrane is spiritual – he introduced African American religious devotion into jazz and created a new aesthetic in the music to facilitate that. Here, that modal, circular approach of John Coltrane is called “African jazz.” Using this as a conduit, Bra Herbie ministered. I had planned to stay only for the first set, but I stayed for the second set as well. And after the show, I noticed that I felt better. The sick feelings had gone away. Did Bra Herbie’s music heal me? Directly, perhaps so. But also, hearing those melodies reminded me of why I am here. I am here to study South African jazz. The accoutrements of my visit are a wonderful blessing, and maybe even necessary, including my church and connected social and family events. But those are not my call to this land. The music of Tenor Player Winston Ngozi called me in 2017 and it was Bra Herbie’s music that called me afresh in early 2022. After hearing “Woza Moya,” at Untitled Basement yesterday, I remembered that day in my bathtub almost two and half years ago at UMass. I am here for this music. For this music, and my African American jazz back home. Home.

After the show, I waited for Bra Khaya to make his way past me on the way to the backstage area. I greeted him for the first time in over a year and a half. As he move forward he said to me with definitive emphasis “you are home!” He is right. When I arrived in New York City back in 2022 my mentor Charles Tolliver said the same thing to me. Home is where I am loved. Home is where I am wanted. Home is where I am claimed. My home is in jazz and with jazz musicians in South Africa and African America. I belong to two places now, both here and there. I am indeed home.